- About

-

Research

- Agronomy and farming systems

-

Agricultural crop research

-

Research projects - agriculture

- About SASSA-SAI

- BioBoost

- Biomass Connect

- CTP for Sustainable Agricultural Innovation

- Climate Ready Beans - workshop presentations (March 2022)

- Crop diversity HPC cluster

- Designing Future Wheat

- Final project workshop

- Get involved

- List of materials

- News and updates

- Partners

- Rustwatch

- The Sentinel Crop Disease Surveillance Network

- The research team

- UK Cereal Pathogen Virulence Survey

- UK wheat varieties pedigree

- Weed management - IWM Praise

- Crop breeding

- Crop characterisation

- Data sciences

- Genetics and pre-breeding

- Plant biotechnology

- Plant pathology and entomology

- Resources

-

Research projects - agriculture

-

Horticultural crop research

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Augmented Berry Vision

- BEESPOKE

- Boosting brassica nutrition in smart growing systems

- CTP for Fruit Crop Research

- Develop user-friendly nutrient demand models

- Egg laying deterrents for spotted wing drosophila

- Enhancing the nutritional quality of tomatoes

- Improving berry harvest forecasts and productivity

- Improving vineyard soil health through groundcover management

- Intelligent growing systems

- Knowledge transfer for sustainable water use

- POME: Precision Orchard Management for Environment

- RASCAL

- STOP-SPOT

- UV-Robot

- Crop science and production systems

- Genetics, genomics and breeding

- Pest and pathogen ecology

- Field vegetables and salad crops

- Plum Demonstration Centre

- The WET Centre

- Viticulture and Oenology

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Crop Science Centre

- Research Projects

-

Services

- Analytical Services

- Business Development

- Commercial trial services

- Membership

- Plant breeding

- Plant characterisation

- Seed certification

-

Training

-

Technical agronomy training

- Advanced crop management of bulb onions

- Advanced crop management of vegetable brassicas

- Advanced nutrient management for combinable crops

- Benefits of cover crops in arable systems

- Best practice agronomy for cereals and oilseed rape

- Developing a Successful Strategy for Spring Crops

- Disease Management and Control in Cereal Crops

- Incorporating SFI options into your rotation

- Protected Environment Horticulture – Best Practice

- Techniques for better pest management in combinable crops

- Crop inspector and seed certification

- Licensed seed sampling

-

Technical agronomy training

- News & Views

- Events

-

Knowledge Hub

- Alternative and break crops

-

Crop genetics

- POSTER: Diversity enriched wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Genetics of wheat flag leaf size (2024)

- POSTER: Wheat yield stability (2024)

- Poster: Traits for future cereal crops (2022)

- POSTER: wild wheat fragment lines (2022)

- POSTER: Improving phenotyping in crop research (2022)

- PRESENTATION: Plant breeding for regen ag

- Poster: Designing Future Wheat (2020)

- Crop nutrition

-

Crop protection

- POSTER: Understanding the hierarchy of black-grass control (2025)

- POSTER: Emerging weed threats (2025)

- POSTER: Disease control in barley (2025)

- Poster: Weed seed predation in regen-ag (2024)

- POSTER: Disease control in winter wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Mode of action (2023)

- POSTER: Inter-row cultivation for black-grass control (2022)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat yellow rust in spring 2025 (2025)

- Poster: Management of Italian ryegrass (2021)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat rusts - 2024/25 review (2025)

- POSTER: UKCPVS disease monitoring and the benefit to UK growers (2025)

- POSTER: Diagnosing and scoring crop disease using AI (2025)

- POSTER: Finding new sources of Septoria resistance (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Detecting air-borne pathogens (2024)

- POSTER: Oilseed rape diseases (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Improving chocolate spot resistance (2022)

- Poster: Pathogen diagnostics (2022)

- Fruit

- Regen-ag & sustainability

-

Seed certification

- POSTER: Wheat DUS (2024)

- POSTER: Innovation in variety testing (2024)

- POSTER: AI and molecular markers for soft fruit (2024)

- POSTER: Barley crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage grass crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage legume crop identification (2024)

- POSTER: Minor cereal crop inspecting (2023)

- POSTER: Pulse crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Wheat crop identification (2023)

-

Soils and farming systems

- POSTER: Checking soil health - across space and time (2024)

- POSTER: Checking soil health - step by step (2024)

- POSTERS: Changing soil management practices (2022)

- Poster: Monitoring natural enemies & pollinators (2021)

- POSTER: Soil structure and organic matter (2024)

- POSTER: Novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2024)

- Video: New Farming Systems project (2021)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- POSTER: Impact of prolonged rainfall on soil structure (2024)

- POSTER: Soil & agronomic monitoring study (2024)

- POSTER: The impact of rotations & cultivations (2024)

- VIDEO: Great Soils; soil sampling guidelines (2020)

- Poster: Soil invertebrates within arable rotations (2024)

- VIDEO: Soil health assessment (2021)

- POSTER: Saxmundham - modern P management learnings

- POSTER: Saxmundham - 125 years of phosphorus management

- Poster: Soil phosphorus - availability, uptake and management (2025)

- POSTER: Morley long term experiments (2025)

- POSTER: Exploiting novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2025)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- Varieties

- About

-

Research

- Agronomy and farming systems

-

Agricultural crop research

-

Research projects - agriculture

- About SASSA-SAI

- BioBoost

- Biomass Connect

- CTP for Sustainable Agricultural Innovation

- Climate Ready Beans - workshop presentations (March 2022)

- Crop diversity HPC cluster

- Designing Future Wheat

- Final project workshop

- Get involved

- List of materials

- News and updates

- Partners

- Rustwatch

- The Sentinel Crop Disease Surveillance Network

- The research team

- UK Cereal Pathogen Virulence Survey

- UK wheat varieties pedigree

- Weed management - IWM Praise

- Crop breeding

- Crop characterisation

- Data sciences

- Genetics and pre-breeding

- Plant biotechnology

- Plant pathology and entomology

- Resources

-

Research projects - agriculture

-

Horticultural crop research

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Augmented Berry Vision

- BEESPOKE

- Boosting brassica nutrition in smart growing systems

- CTP for Fruit Crop Research

- Develop user-friendly nutrient demand models

- Egg laying deterrents for spotted wing drosophila

- Enhancing the nutritional quality of tomatoes

- Improving berry harvest forecasts and productivity

- Improving vineyard soil health through groundcover management

- Intelligent growing systems

- Knowledge transfer for sustainable water use

- POME: Precision Orchard Management for Environment

- RASCAL

- STOP-SPOT

- UV-Robot

- Crop science and production systems

- Genetics, genomics and breeding

- Pest and pathogen ecology

- Field vegetables and salad crops

- Plum Demonstration Centre

- The WET Centre

- Viticulture and Oenology

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Crop Science Centre

- Research Projects

-

Services

- Analytical Services

- Business Development

- Commercial trial services

- Membership

- Plant breeding

- Plant characterisation

- Seed certification

-

Training

-

Technical agronomy training

- Advanced crop management of bulb onions

- Advanced crop management of vegetable brassicas

- Advanced nutrient management for combinable crops

- Benefits of cover crops in arable systems

- Best practice agronomy for cereals and oilseed rape

- Developing a Successful Strategy for Spring Crops

- Disease Management and Control in Cereal Crops

- Incorporating SFI options into your rotation

- Protected Environment Horticulture – Best Practice

- Techniques for better pest management in combinable crops

- Crop inspector and seed certification

- Licensed seed sampling

-

Technical agronomy training

- News & Views

- Events

-

Knowledge Hub

- Alternative and break crops

-

Crop genetics

- POSTER: Diversity enriched wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Genetics of wheat flag leaf size (2024)

- POSTER: Wheat yield stability (2024)

- Poster: Traits for future cereal crops (2022)

- POSTER: wild wheat fragment lines (2022)

- POSTER: Improving phenotyping in crop research (2022)

- PRESENTATION: Plant breeding for regen ag

- Poster: Designing Future Wheat (2020)

- Crop nutrition

-

Crop protection

- POSTER: Understanding the hierarchy of black-grass control (2025)

- POSTER: Emerging weed threats (2025)

- POSTER: Disease control in barley (2025)

- Poster: Weed seed predation in regen-ag (2024)

- POSTER: Disease control in winter wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Mode of action (2023)

- POSTER: Inter-row cultivation for black-grass control (2022)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat yellow rust in spring 2025 (2025)

- Poster: Management of Italian ryegrass (2021)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat rusts - 2024/25 review (2025)

- POSTER: UKCPVS disease monitoring and the benefit to UK growers (2025)

- POSTER: Diagnosing and scoring crop disease using AI (2025)

- POSTER: Finding new sources of Septoria resistance (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Detecting air-borne pathogens (2024)

- POSTER: Oilseed rape diseases (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Improving chocolate spot resistance (2022)

- Poster: Pathogen diagnostics (2022)

- Fruit

- Regen-ag & sustainability

-

Seed certification

- POSTER: Wheat DUS (2024)

- POSTER: Innovation in variety testing (2024)

- POSTER: AI and molecular markers for soft fruit (2024)

- POSTER: Barley crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage grass crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage legume crop identification (2024)

- POSTER: Minor cereal crop inspecting (2023)

- POSTER: Pulse crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Wheat crop identification (2023)

-

Soils and farming systems

- POSTER: Checking soil health - across space and time (2024)

- POSTER: Checking soil health - step by step (2024)

- POSTERS: Changing soil management practices (2022)

- Poster: Monitoring natural enemies & pollinators (2021)

- POSTER: Soil structure and organic matter (2024)

- POSTER: Novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2024)

- Video: New Farming Systems project (2021)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- POSTER: Impact of prolonged rainfall on soil structure (2024)

- POSTER: Soil & agronomic monitoring study (2024)

- POSTER: The impact of rotations & cultivations (2024)

- VIDEO: Great Soils; soil sampling guidelines (2020)

- Poster: Soil invertebrates within arable rotations (2024)

- VIDEO: Soil health assessment (2021)

- POSTER: Saxmundham - modern P management learnings

- POSTER: Saxmundham - 125 years of phosphorus management

- Poster: Soil phosphorus - availability, uptake and management (2025)

- POSTER: Morley long term experiments (2025)

- POSTER: Exploiting novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2025)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- Varieties

Giving up on organic matter

By

Last week I visited Rothamsted Research with a few arable farmers. As always, it was very good value and we were updated on many aspects of the organisation’s research. Pesticide resistance and availability and soil issues were the main themes.

One area that caused particular interest was the evidence behind a new HGCA and Defra funded project on how to get the best out of organic manures. The whole industry is not only aware of the desirability to increase organic matter levels in long-term arable soils but also the futility of trying to achieve such an objective.

Changing to a system of interspersing short periods of arable crops between medium-term grass leys could help but would also have a negative impact on both production and profits. The alternative is to use a lot of organic manures or amendments at regular intervals. However, there are simply not enough of these organic sources to have a significant impact on organic matter levels on more than a very small percentage of our arable land.

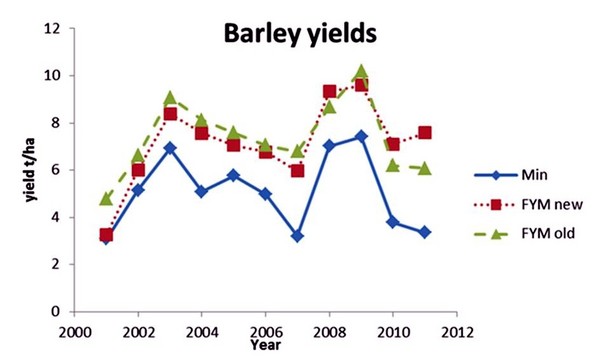

So how best to use these limited organic sources to maximise their benefits? Some research at Rothamsted has provided a clue and is the basis of the new project. Researchers found that the benefits from annual farmyard manure application, in terms of spring barley yields, were quickly available when judged against the same amount of manure being applied annually since 1852 (see figure). This yield benefit, recorded in 2002 after just two successive autumn applications of farmyard manure, could not be explained either by the nutrients in the manure or by an increase in soil organic matter. So what is the possible explanation?

Figure: spring barley yields (t/ha) at the optimum doses of mineral (bag) nitrogen.

The blue line is where mineral nitrogen only has been used annually since 1852, the green line is where both farmyard manure and mineral nitrogen have been used annually since 1852 and the red line is where organic manure and mineral nitrogen have been used annually since 2000 (i.e. first manure application in autumn 2000). Graph kindly provided by Andy Whitmore of Rothamsted Research

Regular readers of my blogs (if there are any out there!) will have guessed the possible explanation because I’ve banged on about this issue before. The application of crop residues and organic manures and amendments increases the level of the biomass of fungal, bacterial and fauna in the soil. These can act as a surrogate for organic matter. However, to maintain these benefits they need annual applications.

It is for this reason that the value of straw to the cereal farmer is more than just the nutrients it contains. Many farmers reported that their land worked more easily after a couple of years of incorporating rather than burning straw. However, despite positive effects on the soil, Rothamsted has not found a benefit in terms of winter wheat yields from the annual incorporation of up to four times the average straw yield.

Why were increased yields recorded from the regular incorporation of organic materials recorded in spring barley and not in winter wheat? It’s my view, which cannot be verified, that spring barley yields are more likely to benefit because the crop is established in more hostile growing conditions and has a shorter growing period. We all recognise that winter wheat yields are more likely than spring barley to compensate for set-backs in the first couple of months of growth. The opposite may well also be true, that spring barley yields more than winter wheat yields are likely to benefit from improved soil conditions in the early stages of establishment.

To continue my theorising, how best should we use the limited UK supplies of organic manures and amendments? Based on very limited information, it would seem that using smaller amounts annually rather than large amounts intermittently in largely spring crop orientated rotations may be the best way forward to maximising yield benefits. However, applying smaller amounts annually will result in extra costs. I’m sure that the Rothamsted project will provide guidance as to the way forward.

Contact

Niab

Park Farm

Villa Road

Histon

Cambridge

CB24 9NZ, UK

Tel: +44(0)1223 342200

Email: [email protected]