- About

-

Research

- Agronomy and farming systems

-

Agricultural crop research

-

Research projects - agriculture

- About SASSA-SAI

- BioBoost

- Biomass Connect

- CTP for Sustainable Agricultural Innovation

- Climate Ready Beans - workshop presentations (March 2022)

- Crop diversity HPC cluster

- Final project workshop

- Get involved

- List of materials

- News and updates

- Partners

- The Sentinel Crop Disease Surveillance Network

- The research team

- UK Cereal Pathogen Virulence Survey

- UK wheat varieties pedigree

- Weed management - IWM Praise

- Crop breeding

- Crop characterisation

- Data sciences

- Genetics and pre-breeding

- Plant biotechnology

- Plant pathology and entomology

- Resources

-

Research projects - agriculture

- Horticultural crop research

- Crop Science Centre

- Research Projects

- Research Publications

-

Services

- Analytical Services

- Business Development

- Commercial trial services

- Membership

- Plant breeding

- Plant characterisation

- Seed certification

-

Training

-

Technical agronomy training

- Advanced crop management of bulb onions

- Advanced crop management of vegetable brassicas

- Advanced nutrient management for combinable crops

- Benefits of cover crops in arable systems

- Best practice agronomy for cereals and oilseed rape

- Developing a Successful Strategy for Spring Crops

- Disease Management and Control in Cereal Crops

- Incorporating SFI options into your rotation

- Protected Environment Horticulture – Best Practice

- Techniques for better pest management in combinable crops

- Crop inspector and seed certification

- Licensed seed sampling

-

Technical agronomy training

- News & Views

- Events

-

Knowledge Hub

- Alternative and break crops

-

Crop genetics

- POSTER: Diversity enriched wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Genetics of wheat flag leaf size (2024)

- POSTER: Wheat yield stability (2024)

- Poster: Traits for future cereal crops (2022)

- POSTER: wild wheat fragment lines (2022)

- POSTER: Improving phenotyping in crop research (2022)

- PRESENTATION: Plant breeding for regen ag

- Poster: Designing Future Wheat (2020)

- Crop nutrition

-

Crop protection

- POSTER: Understanding the hierarchy of black-grass control (2025)

- POSTER: Emerging weed threats (2025)

- POSTER: Disease control in barley (2025)

- Poster: Weed seed predation in regen-ag (2024)

- POSTER: Disease control in winter wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Mode of action (2023)

- POSTER: Inter-row cultivation for black-grass control (2022)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat yellow rust in spring 2025 (2025)

- Poster: Management of Italian ryegrass (2021)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat rusts - 2024/25 review (2025)

- POSTER: UKCPVS disease monitoring and the benefit to UK growers (2025)

- POSTER: Diagnosing and scoring crop disease using AI (2025)

- POSTER: Finding new sources of Septoria resistance (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Detecting air-borne pathogens (2024)

- POSTER: Oilseed rape diseases (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Improving chocolate spot resistance (2022)

- Poster: Pathogen diagnostics (2022)

- Fruit

- Regen-ag & sustainability

-

Seed certification

- POSTER: Wheat DUS (2024)

- POSTER: Innovation in variety testing (2024)

- POSTER: AI and molecular markers for soft fruit (2024)

- POSTER: Barley crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage grass crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage legume crop identification (2024)

- POSTER: Minor cereal crop inspecting (2023)

- POSTER: Pulse crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Wheat crop identification (2023)

-

Soils and farming systems

- POSTER: Checking soil health - across space and time (2024)

- POSTER: Checking soil health - step by step (2024)

- POSTERS: Changing soil management practices (2022)

- Poster: Monitoring natural enemies & pollinators (2021)

- POSTER: Soil structure and organic matter (2024)

- POSTER: Novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2024)

- Video: New Farming Systems project (2021)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- POSTER: Impact of prolonged rainfall on soil structure (2024)

- POSTER: Soil & agronomic monitoring study (2024)

- POSTER: The impact of rotations & cultivations (2024)

- VIDEO: Great Soils; soil sampling guidelines (2020)

- Poster: Soil invertebrates within arable rotations (2024)

- VIDEO: Soil health assessment (2021)

- POSTER: Saxmundham - modern P management learnings

- POSTER: Saxmundham - 125 years of phosphorus management

- Poster: Soil phosphorus - availability, uptake and management (2025)

- POSTER: Morley long term experiments (2025)

- POSTER: Exploiting novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2025)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- Varieties

- About

-

Research

- Agronomy and farming systems

-

Agricultural crop research

-

Research projects - agriculture

- About SASSA-SAI

- BioBoost

- Biomass Connect

- CTP for Sustainable Agricultural Innovation

- Climate Ready Beans - workshop presentations (March 2022)

- Crop diversity HPC cluster

- Final project workshop

- Get involved

- List of materials

- News and updates

- Partners

- The Sentinel Crop Disease Surveillance Network

- The research team

- UK Cereal Pathogen Virulence Survey

- UK wheat varieties pedigree

- Weed management - IWM Praise

- Crop breeding

- Crop characterisation

- Data sciences

- Genetics and pre-breeding

- Plant biotechnology

- Plant pathology and entomology

- Resources

-

Research projects - agriculture

- Horticultural crop research

- Crop Science Centre

- Research Projects

- Research Publications

-

Services

- Analytical Services

- Business Development

- Commercial trial services

- Membership

- Plant breeding

- Plant characterisation

- Seed certification

-

Training

-

Technical agronomy training

- Advanced crop management of bulb onions

- Advanced crop management of vegetable brassicas

- Advanced nutrient management for combinable crops

- Benefits of cover crops in arable systems

- Best practice agronomy for cereals and oilseed rape

- Developing a Successful Strategy for Spring Crops

- Disease Management and Control in Cereal Crops

- Incorporating SFI options into your rotation

- Protected Environment Horticulture – Best Practice

- Techniques for better pest management in combinable crops

- Crop inspector and seed certification

- Licensed seed sampling

-

Technical agronomy training

- News & Views

- Events

-

Knowledge Hub

- Alternative and break crops

-

Crop genetics

- POSTER: Diversity enriched wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Genetics of wheat flag leaf size (2024)

- POSTER: Wheat yield stability (2024)

- Poster: Traits for future cereal crops (2022)

- POSTER: wild wheat fragment lines (2022)

- POSTER: Improving phenotyping in crop research (2022)

- PRESENTATION: Plant breeding for regen ag

- Poster: Designing Future Wheat (2020)

- Crop nutrition

-

Crop protection

- POSTER: Understanding the hierarchy of black-grass control (2025)

- POSTER: Emerging weed threats (2025)

- POSTER: Disease control in barley (2025)

- Poster: Weed seed predation in regen-ag (2024)

- POSTER: Disease control in winter wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Mode of action (2023)

- POSTER: Inter-row cultivation for black-grass control (2022)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat yellow rust in spring 2025 (2025)

- Poster: Management of Italian ryegrass (2021)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat rusts - 2024/25 review (2025)

- POSTER: UKCPVS disease monitoring and the benefit to UK growers (2025)

- POSTER: Diagnosing and scoring crop disease using AI (2025)

- POSTER: Finding new sources of Septoria resistance (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Detecting air-borne pathogens (2024)

- POSTER: Oilseed rape diseases (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Improving chocolate spot resistance (2022)

- Poster: Pathogen diagnostics (2022)

- Fruit

- Regen-ag & sustainability

-

Seed certification

- POSTER: Wheat DUS (2024)

- POSTER: Innovation in variety testing (2024)

- POSTER: AI and molecular markers for soft fruit (2024)

- POSTER: Barley crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage grass crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage legume crop identification (2024)

- POSTER: Minor cereal crop inspecting (2023)

- POSTER: Pulse crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Wheat crop identification (2023)

-

Soils and farming systems

- POSTER: Checking soil health - across space and time (2024)

- POSTER: Checking soil health - step by step (2024)

- POSTERS: Changing soil management practices (2022)

- Poster: Monitoring natural enemies & pollinators (2021)

- POSTER: Soil structure and organic matter (2024)

- POSTER: Novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2024)

- Video: New Farming Systems project (2021)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- POSTER: Impact of prolonged rainfall on soil structure (2024)

- POSTER: Soil & agronomic monitoring study (2024)

- POSTER: The impact of rotations & cultivations (2024)

- VIDEO: Great Soils; soil sampling guidelines (2020)

- Poster: Soil invertebrates within arable rotations (2024)

- VIDEO: Soil health assessment (2021)

- POSTER: Saxmundham - modern P management learnings

- POSTER: Saxmundham - 125 years of phosphorus management

- Poster: Soil phosphorus - availability, uptake and management (2025)

- POSTER: Morley long term experiments (2025)

- POSTER: Exploiting novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2025)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- Varieties

Wheat yields 2018

By

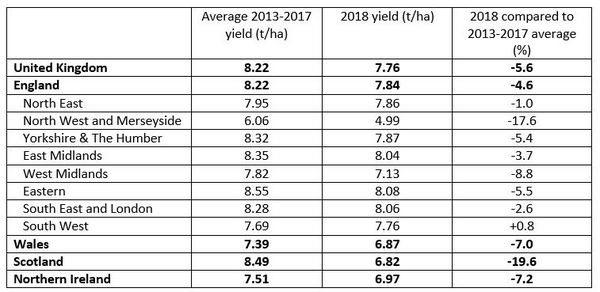

The summer of 2018 is clearly summed up by the autumnal picture of a banana tree in Clare College gardens, just down river from our house in Cambridge. It was hot and also it was very dry from late April onwards. In the UK, dry summers are often associated  with high wheat yields but in my blog, written in early July (blog posted on 13 July), I suggested that it might perhaps prove too dry in 2018 and that wheat yields could be significantly down on average. The Defra statistics, released just before Christmas, show that yields were down by around 6% in the UK and 5% in England (see Table), when compared to the average yield for the previous five years.

with high wheat yields but in my blog, written in early July (blog posted on 13 July), I suggested that it might perhaps prove too dry in 2018 and that wheat yields could be significantly down on average. The Defra statistics, released just before Christmas, show that yields were down by around 6% in the UK and 5% in England (see Table), when compared to the average yield for the previous five years.

So how good was my prediction? I suppose it all depends on what is meant by ‘significant’. I must admit that I was pleasantly surprised by the overall yields but some farms in the very driest parts of the country were well down. In East Anglia much depended on the amount of rain that fell in the last week of May. The West Midland regional yield was down by 9% compared to the average of the previous five harvests. The late spring and summer was particularly hot and dry in that region and the lighter soils, in particular, must have suffered.

In Scotland and the North West of England yields were down by around 18-20%. Unlike the rest of England, the establishment conditions in these areas were far from ideal and the growing conditions during the winter and early spring were hostile to plant growth. As a result the wheat crop was poorly developed when the drought conditions occurred.

As one would expect, second wheats were often particularly low in yield. In this rotational situation one would normally expect antagonistic soil biota to reduce root growth and hence restrict access to soil water during the prevailing extremely dry conditions.

Perhaps I can tentatively congratulate myself on my prediction if a reduction in average yield of 6% can be called ‘significant’. On the other hand, it may be that I have again over-estimated the impact of dry conditions on final yields. As I have said in previous blogs, solar radiation is typically above average in dry summers and this can more than compensate for a moderate lack of moisture. However, this year was so hot and dry that the very high levels of solar radiation could not compensate for the impact of high soil moisture deficits and for the much shorter period of grain fill that occurred as a result of the high average temperatures.

As I mentioned in my previous blog, the drought in the summer of 2018 was less severe than in 1976 when I was seeing crops showing drought symptoms as early as the end of April. In contrast, at that time of year in 2018 the soil moisture deficits were low or non-existent. This may explain why UK average wheat yields were down by 12% in 1976 rather than the 6% of this year. So, it could have been worse! Overall we must be very thankful that our wheat yields are so resilient from year to year.

Contact

Niab

Park Farm

Villa Road

Histon

Cambridge

CB24 9NZ, UK

Tel: +44(0)1223 342200

Email: [email protected]